“If I can’t dance to it, I don’t want your revolution”. Supposedly that was said by a young Emma Goldman in the early 20th century (quite possibly she never actually said it, but it’s a good line so I’m sure she doesn’t mind taking credit). Since then, there have been plenty of people claiming the struggle for social change is all work and no play, but there have also been plenty of people who like Emma, believe that protest and party can go together.

The 1960’s is an era commonly associated with both partying and protest, but its not exactly clear how often the two were in a mutually beneficial relationship – Timothy Leary’s “tune in and drop out” proselytising of LSD was often anti-political; while Woodstock, for all its mythology, was a for-profit rock concert – people got in for free only because they tore down the fences erected by festival organisers. One of the points when party and politics met at that festival was when activist Abbie Hoffman bumrushed the stage to inject some radicalism. “I think this is a pile of shit while John Sinclair rots in prison!” he yelled. Guitarist of The Who Pete Townshend yelled “fuck off my fucking stage” and hit him over the head with his guitar. The crowd cheered.

John Sinclair and Abbie  Hoffman though are two 60’s figures who really tried to combine protest and party. Sinclair formed the White Panther Party, whose propaganda came from heavy rock band the MC5 and whose manifesto was “dope, guns and fucking in the streets”; Hoffman and his group the Yippees staged hippie “be-ins” at the Pentagon and sent Wall St into chaos by showering the stock market floor with dollar bills. In 1968 at the height of the Vietnam war, Sinclair and Hoffman among others organised a protest outside the Democrat convention in Chicago. In response to the “national death party”, they called it “the festival of life” – the invitation said:

Hoffman though are two 60’s figures who really tried to combine protest and party. Sinclair formed the White Panther Party, whose propaganda came from heavy rock band the MC5 and whose manifesto was “dope, guns and fucking in the streets”; Hoffman and his group the Yippees staged hippie “be-ins” at the Pentagon and sent Wall St into chaos by showering the stock market floor with dollar bills. In 1968 at the height of the Vietnam war, Sinclair and Hoffman among others organised a protest outside the Democrat convention in Chicago. In response to the “national death party”, they called it “the festival of life” – the invitation said:

“Rise up and abandon the creeping meatball! Come all you rebels, youth spirits, rock minstrels, truth seekers, peacock freaks, poets, barricade jumpers, dancers, lovers and artists… We demand a politics of ecstasy.”

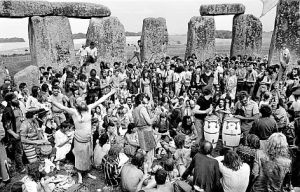

The UK equivalent of Woodstock was the Isle Of Wight festival in 1970. Like Woodstock though there was a tension between party and protest. A group calling itself the British White Panthers broke through the fence, opening it up to all comers. Far from a one-off example though, that festival invasion was part of a “free festival” movement of radical parties. Most free festivals occurred unpermitted and often led to clashes with police – the Windsor Free Festival (which was billed as a “rent strike” and intentionally held “in the Queen’s back garden”) was violently broken up; the Stonehenge festival famously ended in the “battle of Beanfield” between police and partiers in 1985. Free festival organisers saw them as potential not just for great parties, but for radical transformation. One flyer from 1980 said

“Free festivals are practical demonstrations of what society could be like all the time: miniature utopias of joy and communal awareness rising for a few days from a grey morass of mundane, inhibited, paranoid and repressive everyday existence…The most lively [young people] escape geographically and physically to the ‘Never Never Land’ of a free festival where they become citizens, indeed rulers, in a new reality.”

“Free festivals are practical demonstrations of what society could be like all the time: miniature utopias of joy and communal awareness rising for a few days from a grey morass of mundane, inhibited, paranoid and repressive everyday existence…The most lively [young people] escape geographically and physically to the ‘Never Never Land’ of a free festival where they become citizens, indeed rulers, in a new reality.”

While some free festivals struggled against violent policing, some were co-opted into the not-free festival world (eg. A little festival you may have heard of called Glastonbury). But the energy lived on and the rise of electronic music led to a revival in the early 90’s. Underground raves (what we in Australia onomatopoeically call “bush doofs”) were so huge in the UK that the Tory government passed the Criminal Justice Act of 1994 – a law that gave police powers to shut down any outdoor event where ‘”music” (inverted commas actually in the law!) includes sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats’.

There were massive protests (and more clashes with police) against the laws. But somewhere between the idealism of the parties and the radicalisation of being criminalised just for being young and having fun; the rave scene built links with the radical squatters scene and the anti-roads campaign against new highways that destroyed forests or communities. The most famous was the

There were massive protests (and more clashes with police) against the laws. But somewhere between the idealism of the parties and the radicalisation of being criminalised just for being young and having fun; the rave scene built links with the radical squatters scene and the anti-roads campaign against new highways that destroyed forests or communities. The most famous was the  weeklong eviction resistance of the Claremont Rd squats in east London set up against the M11 highway. In Harry McIntosh’s very entertaining account of the blockade, he describes how after police turned off power and shut down the sound system on the first day, power was restored via an underground tunnel to the blockade; keeping the party going. “In the face of anti-rave and protest laws techno continues to provide the rebel soundtrack for the British 90’s.”

weeklong eviction resistance of the Claremont Rd squats in east London set up against the M11 highway. In Harry McIntosh’s very entertaining account of the blockade, he describes how after police turned off power and shut down the sound system on the first day, power was restored via an underground tunnel to the blockade; keeping the party going. “In the face of anti-rave and protest laws techno continues to provide the rebel soundtrack for the British 90’s.”

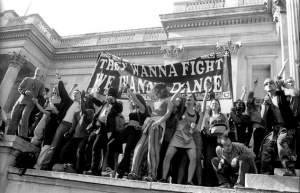

Out of the anti-roads movement came the idea of Reclaim The Streets – parties that invade and shut down major roads to either protest specific issues or just to open up new spaces (physical and mental) for creative use. Reclaim The Streets became strongly linked with the anti-globalisation movement of the early 2000’s that would attempt to shut down global trade meetings.

Recent documentary Do It Ourselves traced the history of Reclaim The Streets, underground raves and protest partying in Australia. That history is still kept alive in events like recent “protestivals” at the Olympic Dam uranium mine and some of the experiments in “tactical urbanism” by groups like Brisbane’s Right To The City.

Part of that tradition though has also transmuted into commercial raves and bush doofs – scenes that have taken on the music and aesthetic but not the ideals. Many participants would have no idea of the scene’s links with radical politics. It should be said that there’s nothing inherently radical about partying – especially in the hedonistic world of 21st century consumer capitalism. That tension between those want to fight the power and those who just want to fight for the right to party still exists.

has also transmuted into commercial raves and bush doofs – scenes that have taken on the music and aesthetic but not the ideals. Many participants would have no idea of the scene’s links with radical politics. It should be said that there’s nothing inherently radical about partying – especially in the hedonistic world of 21st century consumer capitalism. That tension between those want to fight the power and those who just want to fight for the right to party still exists.

To really be revolutionary, our parties and festivals need to in some way build links to movements that can actually change our social conditions or environment; movements that can include people beyond the young white demographic of much of the party attendees. They need to also hold an awareness that while some of us are lucky enough to spend our time partying, others don’t have that luxury – they may in fact be slaving away for long, dangerous and underpaid hours soldering our sound systems or sewing our cool party outfits. For many, partying is something that happens in opposition to protest – people are actively hostile to collective organising for a better world and instead espouse new age/conspiracy ideas.

Partying in itself will never bring about a revolution. And yet I can’t help but feel that neither will endless political rallies and meetings, perfectly formulated theories or campaign strategies. Music, art and partying can change political consciousness – being experiential they can penetrate to where no theory can reach. They can help us to envision alternative possibilities for the future and the present, and in a tiny way can create models of another world.

And you know what? The best parties always have an element of revolution in them, and the best protests always have a bit of partying. The struggle goes on for a revolution we can dance to.

Another great piece of writing, Andy.

Pingback: 10 OF THE BEST – MC5

Pingback: 10 OF THE BEST – MC5 | Johnsinclair.us